Meteorological Normalisation with {deweather}

Source:vignettes/articles/deweather.Rmd

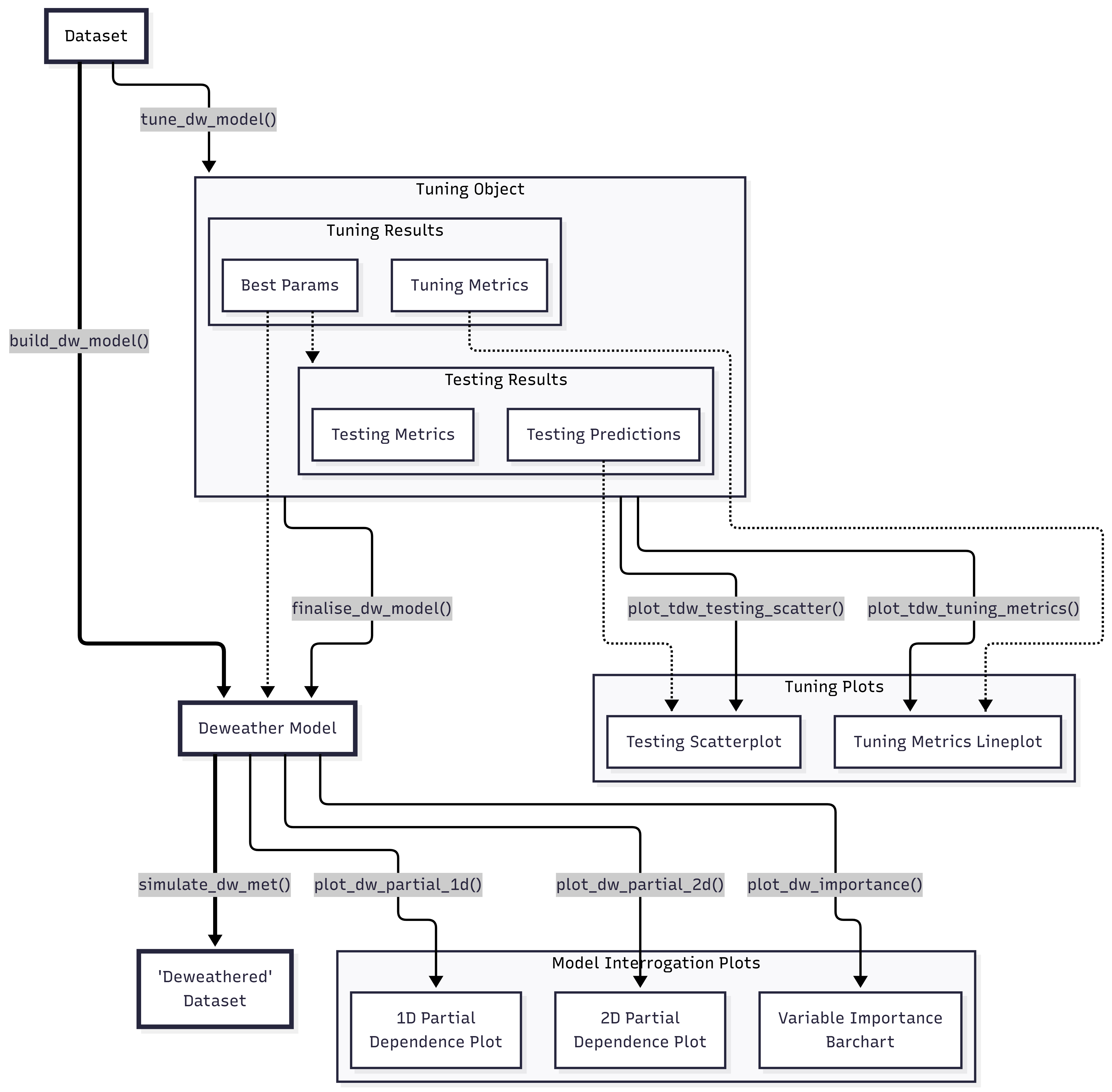

deweather.RmdIntroduction

Meteorology plays a central role in affecting the concentrations of pollutants in the atmosphere. When considering trends in air pollutants it can be very difficult to know whether a change in concentration is due to emissions or meteorology.

By default, the deweather package uses a powerful statistical technique based on boosted regression trees using a variety of packages using the tidymodels framework. This allows for a variety of engines to be employed, with the default being xgboost. Statistical models are developed to explain concentrations using meteorological and other variables. These models can be tested on randomly withheld data with the aim of developing the most appropriate model.

Much of deweather supports parallel processing with the mirai package, so along with loading the library we’ll set some daemons as well as a seed.

Example data set

The deweather package comes with a comprehensive

data set of air quality and meteorological data. The air quality data is

from Marylebone Road in central London (obtained from the

openair package) and the meteorological data from

Heathrow Airport (obtained from the worldmet package).

The aqroadside data frame contains various pollutants such

a NOx, NO2, ethane and isoprene as well as

meteorological data including wind speed, wind direction, relative

humidity, ambient temperature and cloud cover.

head(aqroadside)

#> # A tibble: 6 × 11

#> date nox no2 ethane isoprene benzene ws wd air_temp

#> <dttm> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 2000-01-01 00:00:00 388 78 13.5 1.22 7.74 2.1 200 7.4

#> 2 2000-01-01 01:00:00 886 84 12.0 0.85 5.66 2.1 190 7.83

#> 3 2000-01-01 02:00:00 816 117 14.7 1.75 11.4 1.8 215 7.95

#> 4 2000-01-01 03:00:00 636 97 20.4 4.36 30.8 1.25 240 8.05

#> 5 2000-01-01 04:00:00 483 74 18.8 3.08 19.7 1.55 260 8.6

#> 6 2000-01-01 05:00:00 231 65 16.4 2.12 13.1 2.35 270 8.35

#> # ℹ 2 more variables: rh <dbl>, cl <dbl>Prepare for Model Building

A straightforward way to get started is to use the

append_dw_vars() function to attach a load of useful model

features to your air quality data.frame. Variables such as

the hour of the day ("hour") and day of the week

("weekday") are used as features to explain some of the

variation. "hour" for example very usefully acts as a proxy

for the diurnal variation in emissions. These temporal emission proxies

are also important to include to help the model differentiate between

emission versus weather-related changes. For example, emissions tend to

change throughout a day and so do variables such as wind speed and

ambient temperature (here already present in the data as

"ws" and "air_temp" respectively).

Note that, strictly, append_dw_vars() does not need to

be run directly; if build_dw_model() or

tune_dw_model() are passed any of "hour",

"weekday", "trend", "yday",

"week", or "month" to vars, the

parent function will use append_dw_vars() itself in the

background if those columns do not exist in the input dataframe.

append_dw_vars(aqroadside) |>

dplyr::glimpse()

#> Rows: 149,040

#> Columns: 18

#> $ date <dttm> 2000-01-01 00:00:00, 2000-01-01 01:00:00, 2000-01-01 02:00:0…

#> $ nox <dbl> 388, 886, 816, 636, 483, 231, 380, 287, 187, 111, 149, 132, 3…

#> $ no2 <dbl> 78, 84, 117, 97, 74, 65, 67, 69, 67, 57, 57, 57, 82, 84, 76, …

#> $ ethane <dbl> 13.54, 11.99, 14.69, 20.38, 18.75, 16.38, 16.16, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ isoprene <dbl> 1.22, 0.85, 1.75, 4.36, 3.08, 2.12, 1.25, NA, NA, NA, NA, 0.4…

#> $ benzene <dbl> 7.74, 5.66, 11.38, 30.75, 19.66, 13.13, 7.64, NA, NA, NA, NA,…

#> $ ws <dbl> 2.10, 2.10, 1.80, 1.25, 1.55, 2.35, 1.80, 1.00, 0.50, 0.00, 0…

#> $ wd <dbl> 200, 190, 215, 240, 260, 270, 260, 250, 240, NA, 210, 275, 26…

#> $ air_temp <dbl> 7.400000, 7.833333, 7.950000, 8.050000, 8.600000, 8.350000, 8…

#> $ rh <dbl> 97.33482, 97.15970, 99.00136, 98.67437, 95.11393, 97.71058, 9…

#> $ cl <dbl> 5.0, 6.0, 4.5, 4.5, 7.5, 5.5, 8.0, 4.0, 1.5, 2.5, 4.0, 7.0, 4…

#> $ trend <dbl> 946684800, 946688400, 946692000, 946695600, 946699200, 946702…

#> $ hour <int> 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17,…

#> $ weekday <fct> Sat, Sat, Sat, Sat, Sat, Sat, Sat, Sat, Sat, Sat, Sat, Sat, S…

#> $ weekend <fct> weekend, weekend, weekend, weekend, weekend, weekend, weekend…

#> $ yday <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1…

#> $ week <int> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1…

#> $ month <fct> Jan, Jan, Jan, Jan, Jan, Jan, Jan, Jan, Jan, Jan, Jan, Jan, J…Build a Model

Tuning a Model

There are many input parameters to build_dw_model() and,

while sensible defaults have been set, you may be interested in seeing

how tweaking them can influence how well the model behaves. This is

called “tuning”, and the tune_dw_model() function provides

an interface for this. Any of the boosted decision tree parameters

(e.g., tree_depth and trees) can be set as a

range which is then combined with grid_levels to create a

regular grid of all parameter combinations.

Note that this process can take a while, especially if many

parameters are being tuned. One way to speed this up is to invoke

parallel processing through the mirai package - see https://tune.tidymodels.org/articles/extras/optimizations.html#parallel-processing

for more information. In this example, we’ll also significantly trim

down the data to speed things up.

tuned_results <-

aqroadside |>

# want to sample by weekday to get good spread of categorical data

append_dw_vars("weekday") |>

dplyr::slice_sample(n = 250, by = weekday) |>

# tune model

tune_dw_model(

pollutant = "no2",

tree_depth = c(1, 5),

min_n = c(5, 10),

grid_levels = 3L

)This output has a few useful features. First, we’re informed that the

best value for trees is 50 and for tree_depth

is 5.

get_tdw_best_params(tuned_results)

#> $min_n

#> [1] 10

#>

#> $tree_depth

#> [1] 5

#>

#> $trees

#> [1] 50

#>

#> $mtry

#> NULL

#>

#> $learn_rate

#> [1] 0.1

#>

#> $loss_reduction

#> [1] 0

#>

#> $sample_size

#> [1] 1

#>

#> $stop_iter

#> [1] 45

#>

#> $alpha

#> [1] 0

#>

#> $lambda

#> [1] 1If we want to interrogate this more, the metrics object

shows a summary for all of the different hyperparameters that have been

tuned. Examining the full set of metrics, rather than only the single

best configuration, allows you to assess whether the marginal

performance gain of the “best” model justifies its additional

computational cost or complexity. For example, with air quality

timeseries data, its likely that increasing trees (the

number of trees in the model) is always going to ‘improve’ the model,

but the actual benefits may be marginal after a certain threshold and

only serve to increase the time taken to fit and use the finalised

model.

get_tdw_tuning_metrics(tuned_results)

#> # A tibble: 18 × 6

#> min_n tree_depth metric mean n std_err

#> <int> <int> <chr> <dbl> <int> <dbl>

#> 1 5 1 rmse 37.5 10 0.850

#> 2 5 1 rsq 0.443 10 0.0173

#> 3 5 3 rmse 31.2 10 0.720

#> 4 5 3 rsq 0.599 10 0.0200

#> 5 5 5 rmse 29.7 10 0.728

#> 6 5 5 rsq 0.628 10 0.0194

#> 7 7 1 rmse 37.5 10 0.850

#> 8 7 1 rsq 0.443 10 0.0173

#> 9 7 3 rmse 31.1 10 0.693

#> 10 7 3 rsq 0.600 10 0.0201

#> 11 7 5 rmse 29.6 10 0.645

#> 12 7 5 rsq 0.632 10 0.0199

#> 13 10 1 rmse 37.5 10 0.850

#> 14 10 1 rsq 0.443 10 0.0173

#> 15 10 3 rmse 31.1 10 0.661

#> 16 10 3 rsq 0.601 10 0.0197

#> 17 10 5 rmse 29.5 10 0.651

#> 18 10 5 rsq 0.633 10 0.0201It can be useful to see this data in a plot; the

plot_tdw_tuning_metrics() function allows for this to be

done fairly flexibly. Note that this function is likely of most use with

between 1 and 3 tuned hyperparmaeters; any more and its likely to be too

messy to be interpretable. It may be useful to look for the ‘elbow’ in

the data, where the decrease in RMSE or increase in RSQ goes from a

large gradient to a small one. Around this elbow is likely a good value

to set your hyperparameter.

plot_tdw_tuning_metrics(tuned_results, x = "tree_depth", group = "min_n")

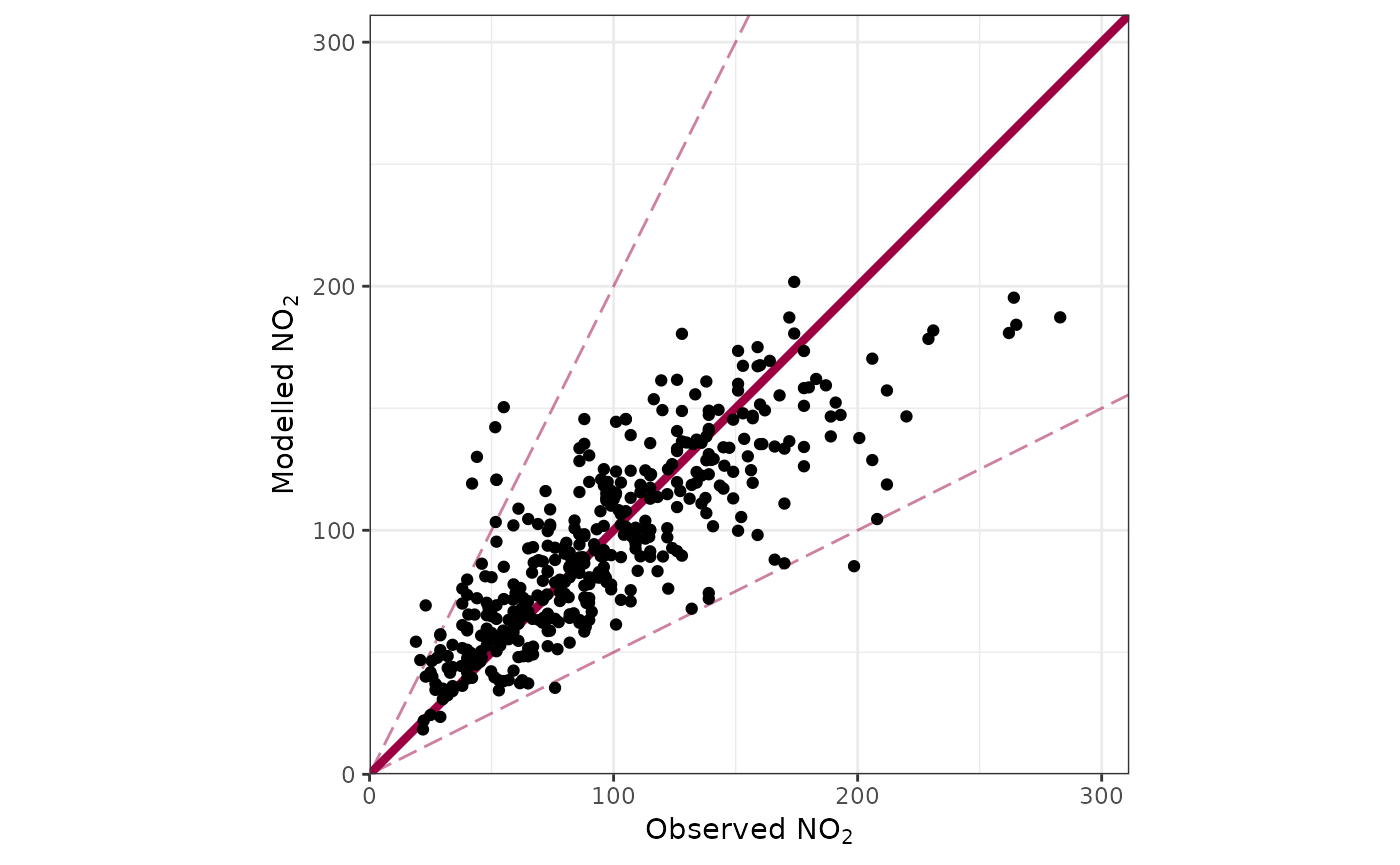

We can also see how the tuned model behaved on some reserved testing data, using the ‘best parameters’ it has decided on. A set of predictions is included (which can be usefully plotted as a scatter chart or binned surface), as well as a set of metrics to evaluate.

get_tdw_testing_metrics(tuned_results) |>

dplyr::glimpse()

#> List of 11

#> $ n : int 424

#> $ fac2: num 0.965

#> $ mb : num -0.718

#> $ mge : num 20.1

#> $ nmb : num -0.00755

#> $ nmge: num 0.212

#> $ rmse: num 28

#> $ r : num 0.812

#> $ p : num 6.76e-101

#> $ coe : num 0.467

#> $ ioa : num 0.733

plot_tdw_testing_scatter(tuned_results)

Finalising a Model

Assuming that a good model can be developed, it can now be explored

in more detail. deweather has useful defaults for many of

the model parameters, but these can be adjusted by the user if

required.

no2_model <-

build_dw_model(

data = aqroadside,

pollutant = "no2",

vars = c("trend", "ws", "wd", "hour", "weekday", "air_temp"),

engine = "xgboost"

)Alternatively, if you have carried out some model tuning, you can use

the finalise_tdw_model() function to automatically lift the

‘best’ parameters from that.

no2_model_alt <- finalise_tdw_model(tuned_results, aqroadside)Both of these functions return a “deweather model” object. We can see a quick summary of it by simply printing it.

no2_model

#>

#> ── Deweather Model ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────

#> A model for predicting no2 using wd (43.9%), hour (29.0%), trend (10.8%),

#> weekday (8.4%), ws (5.8%), and air_temp (2.0%).

#>

#> ── Model Parameters ──

#>

#> • tree_depth: 5

#> • trees: 50

#> • learn_rate: 0.1

#> • mtry: NULL

#> • min_n: 10

#> • loss_reduction: 0

#> • sample_size: 1

#> • stop_iter: 45We can also pull out specific features of the model using

get_dw_*() functions. deweather has many of

such ‘getter’ functions, and they form a consistent, useful API for

accessing relevant features of different objects created in the

package.

get_dw_pollutant(no2_model)

#> [1] "no2"

get_dw_vars(no2_model)

#> [1] "trend" "ws" "wd" "hour" "weekday" "air_temp"

get_dw_input_data(no2_model)

#> # A tibble: 144,535 × 7

#> no2 trend ws wd hour weekday air_temp

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <fct> <dbl>

#> 1 78 946684800 2.1 200 0 Sat 7.4

#> 2 84 946688400 2.1 190 1 Sat 7.83

#> 3 117 946692000 1.8 215 2 Sat 7.95

#> 4 97 946695600 1.25 240 3 Sat 8.05

#> 5 74 946699200 1.55 260 4 Sat 8.6

#> 6 65 946702800 2.35 270 5 Sat 8.35

#> 7 67 946706400 1.8 260 6 Sat 8.2

#> 8 69 946710000 1 250 7 Sat 7.1

#> 9 67 946713600 0.5 240 8 Sat 6.2

#> 10 57 946720800 0.5 210 10 Sat 6.9

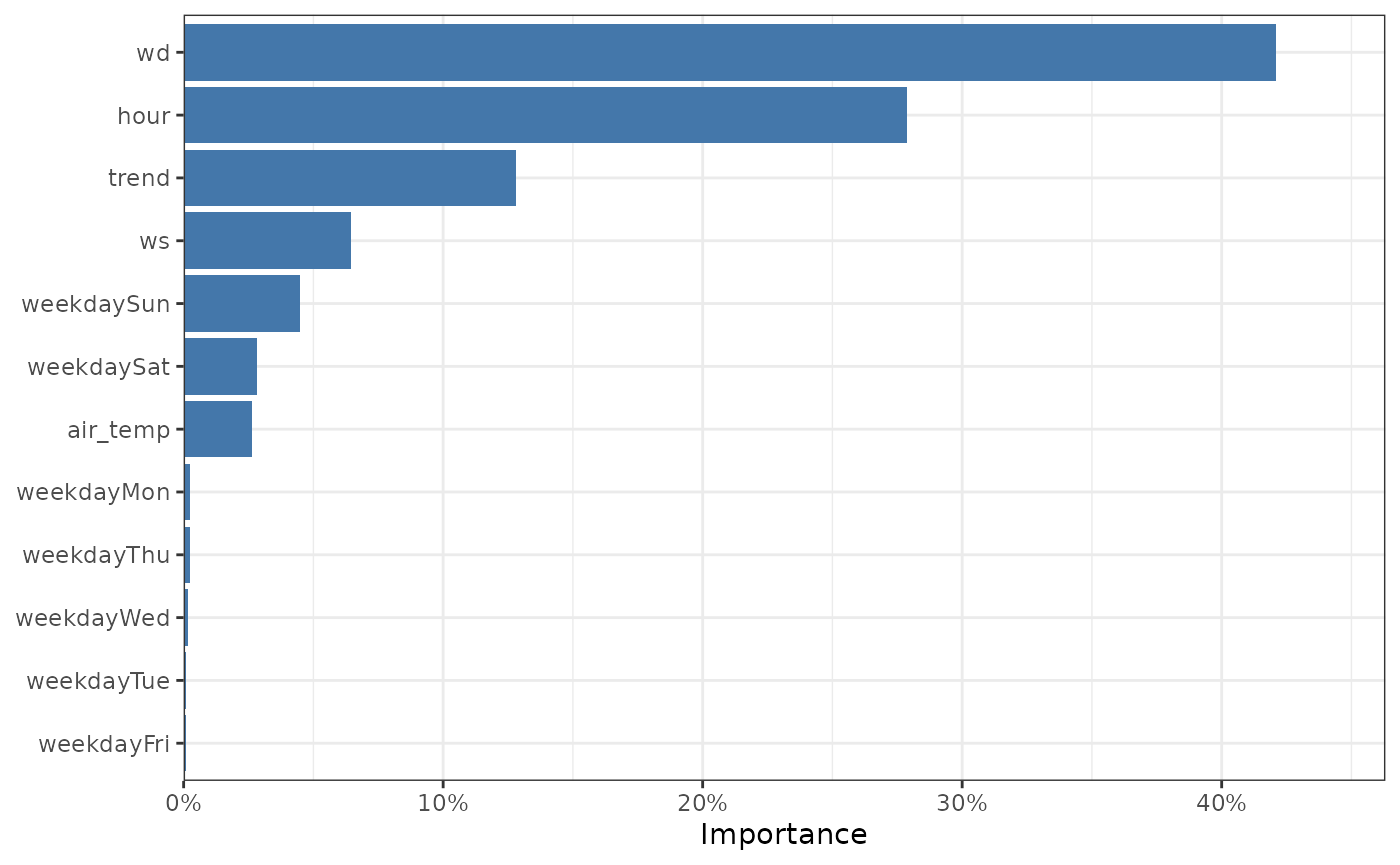

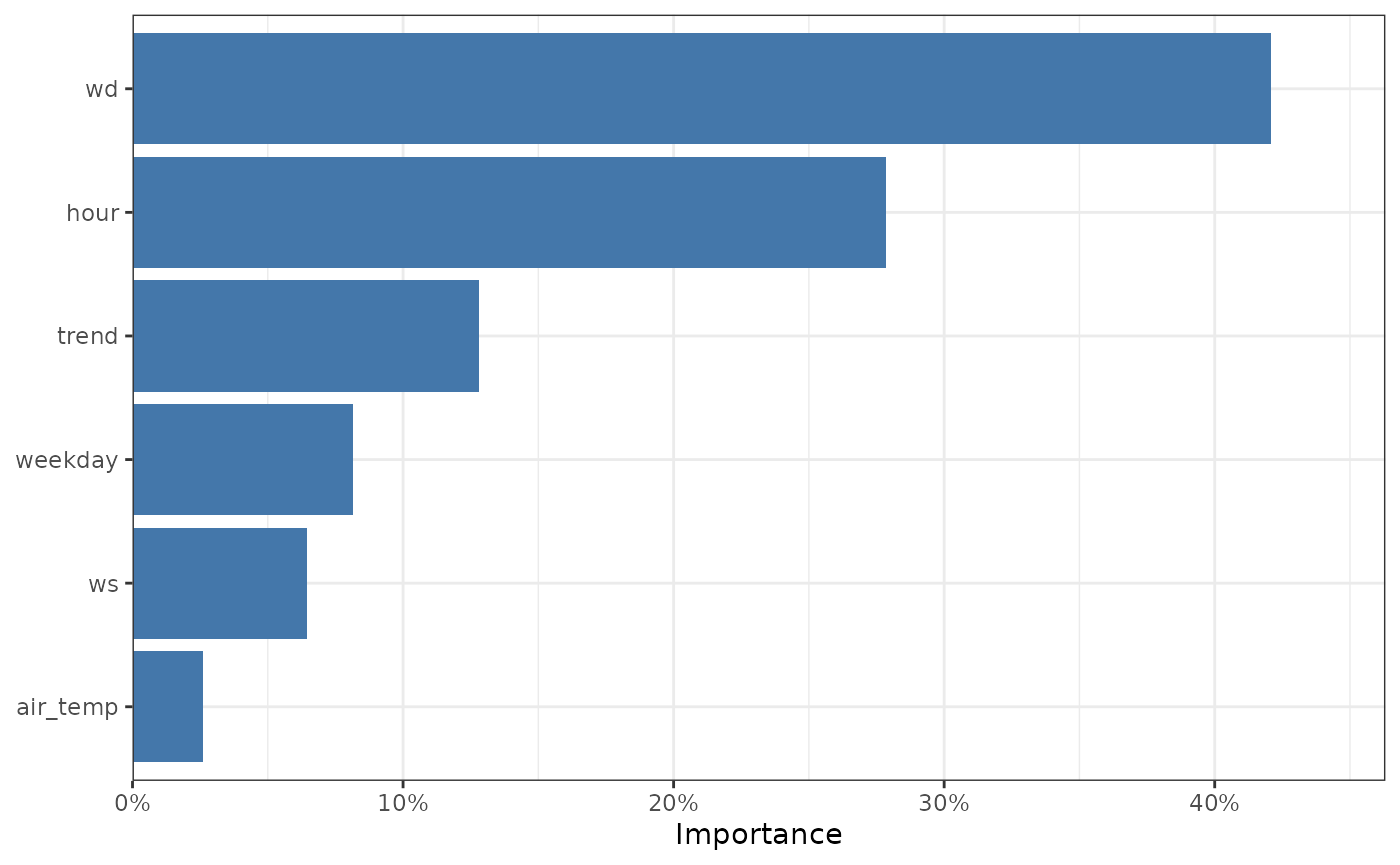

#> # ℹ 144,525 more rowsOne feature we immediately have access to is the “feature importance”

score. This can be obtained as a data.frame using a similar

approach to the above. This varies depending on the chosen

engine, but for boosted trees this represents ‘Gain’ - the

fractional contribution of each feature to the model based on the total

gain of this feature’s splits. A higher percentage means a more

important predictive feature.

get_dw_importance(no2_model)

#> # A tibble: 12 × 2

#> var importance

#> <fct> <dbl>

#> 1 wd 0.439

#> 2 hour 0.290

#> 3 trend 0.108

#> 4 ws 0.0583

#> 5 weekdaySun 0.0479

#> 6 weekdaySat 0.0296

#> 7 air_temp 0.0196

#> 8 weekdayMon 0.00216

#> 9 weekdayThu 0.00166

#> 10 weekdayWed 0.00108

#> 11 weekdayTue 0.000806

#> 12 weekdayFri 0.000550The Gain can be automatically plotted as a bar chart using the

plot_dw_importance() function. The wind direction is the

most predictive feature, and the day of the week being any week day is

the least predictive feature.

plot_dw_importance(no2_model)

The feature importance of our model.

You’ll notice that our ‘character’ variable, the day of the week, has

been split out into multiple levels. This is because

xgboost requires numeric variables, so behind the scenes

our ‘day of the week’ variable is split out into a matrix of seven

variables. This is informative - for example, we can see here that the

day of the week being a weekend is a useful feature. Regardless, if you

would like to see factor features as single features, the

aggregate_factors argument may be of use.

plot_dw_importance(no2_model, aggregate_factors = TRUE)

The feature importance of our model, with factors aggregated.

Examine the partial dependencies

Basic PD Plots

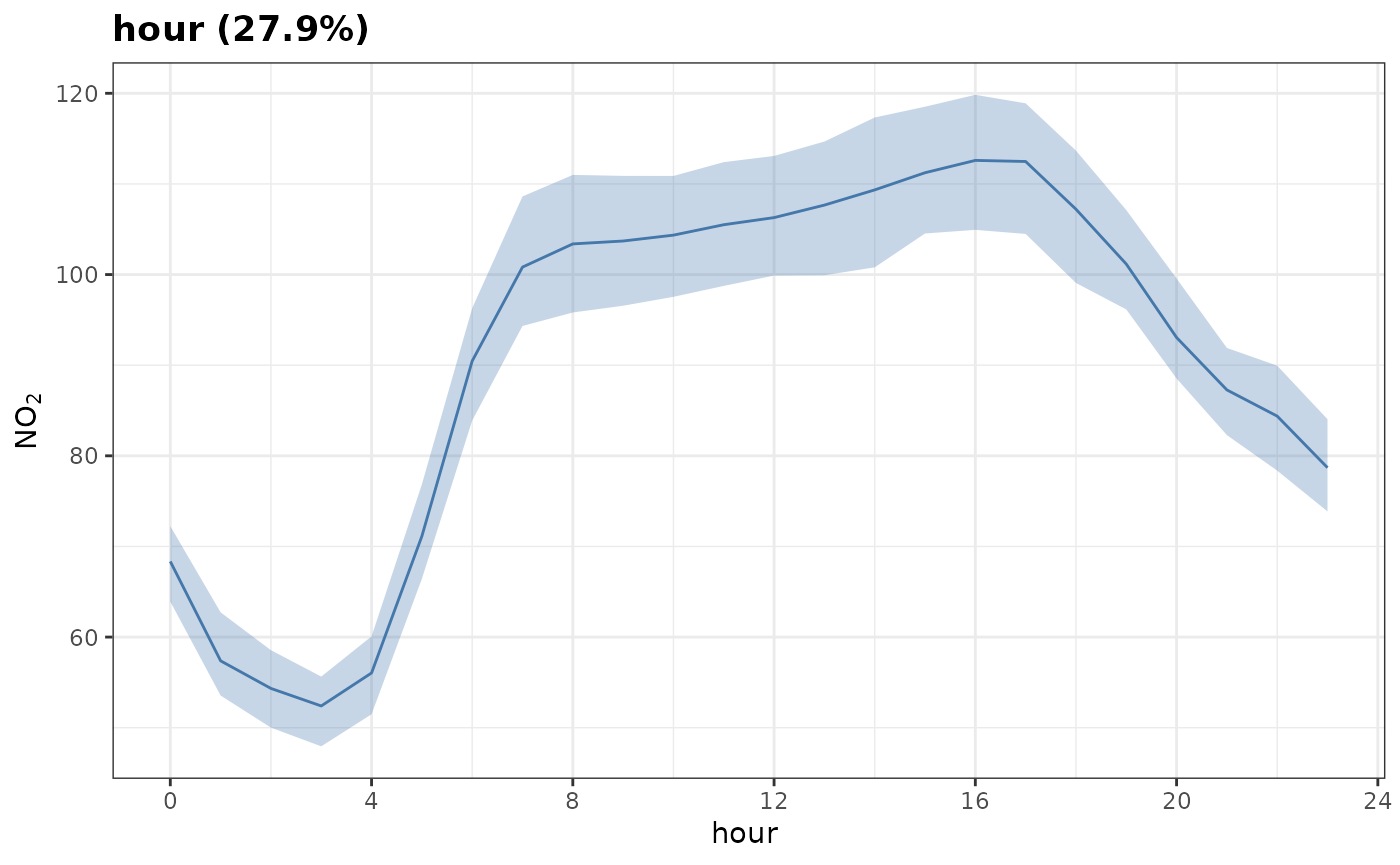

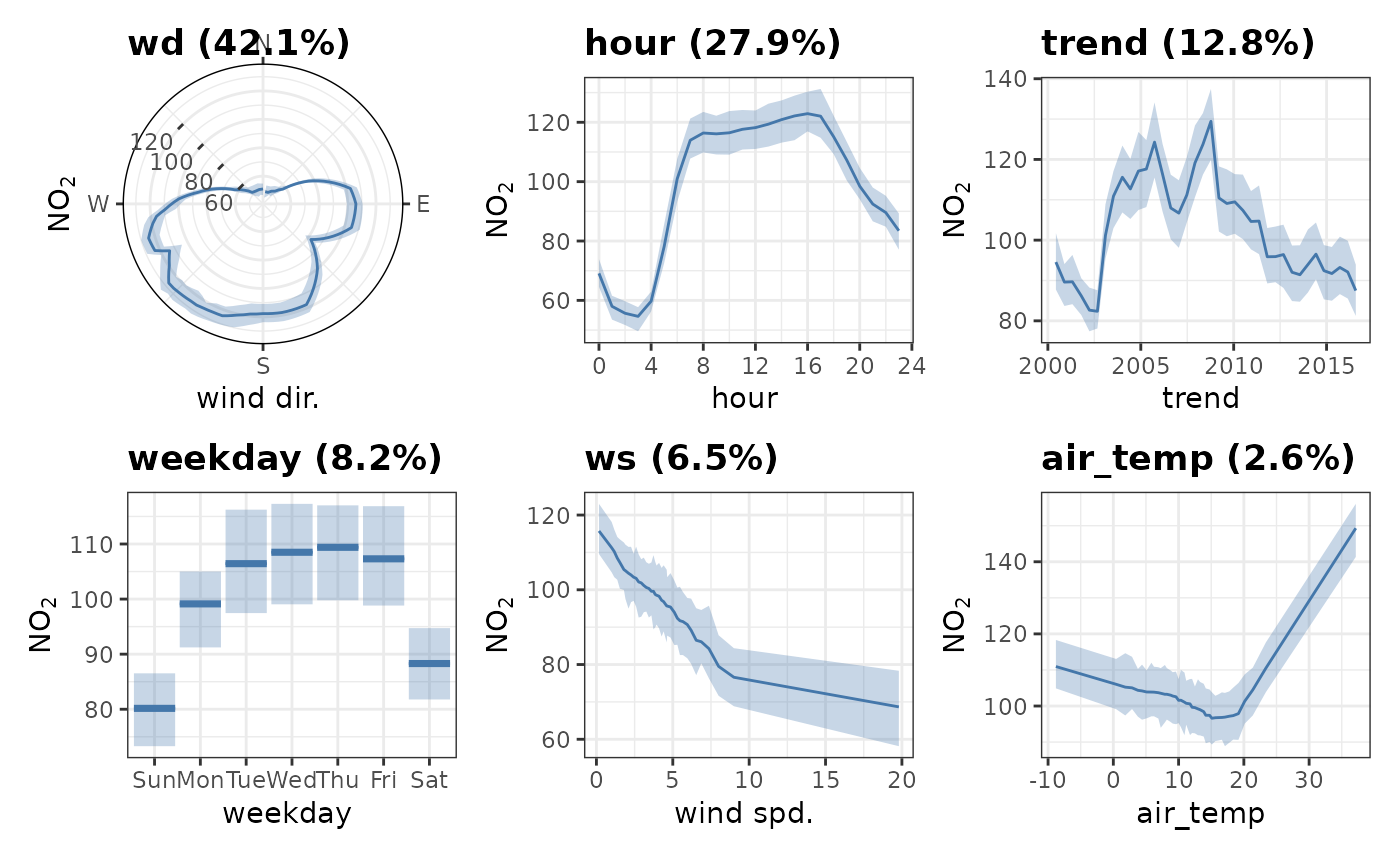

One of the benefits of the boosted regression tree approach is that the partial dependencies can be explored. In simple terms, the partial dependencies show the relationship between the pollutant of interest and the covariates used in the model while holding the value of other covariates at their mean level.

Lets plot a partial dependency for the hour variable.

We’ll set n to 100 for speed; this will sample

100 random samples of our original data to construct the plot. We can

see that no2 is highest during the day and lowest

overnight, everything else kept equal.

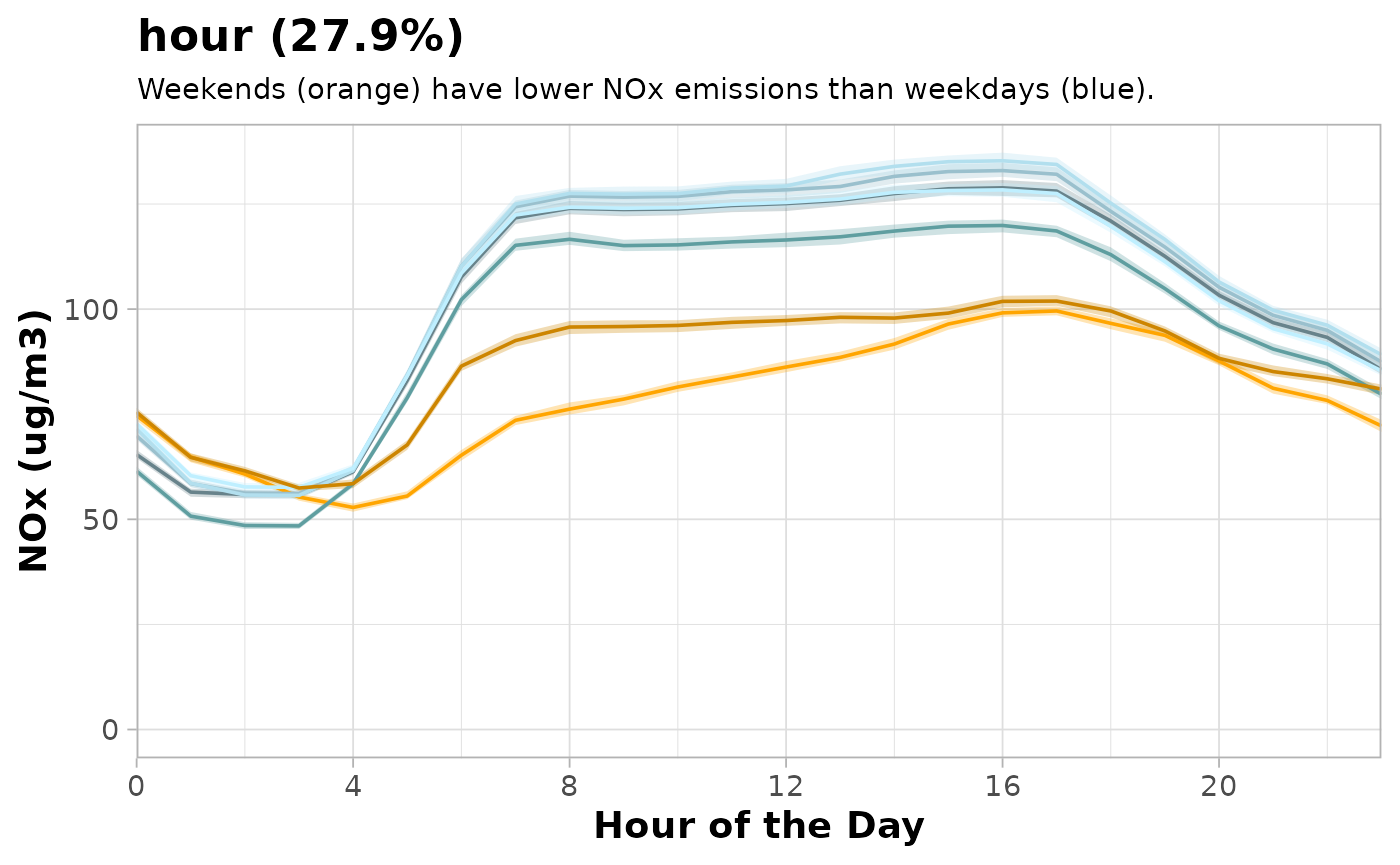

plot_dw_partial_1d(no2_model, "hour", n = 100)

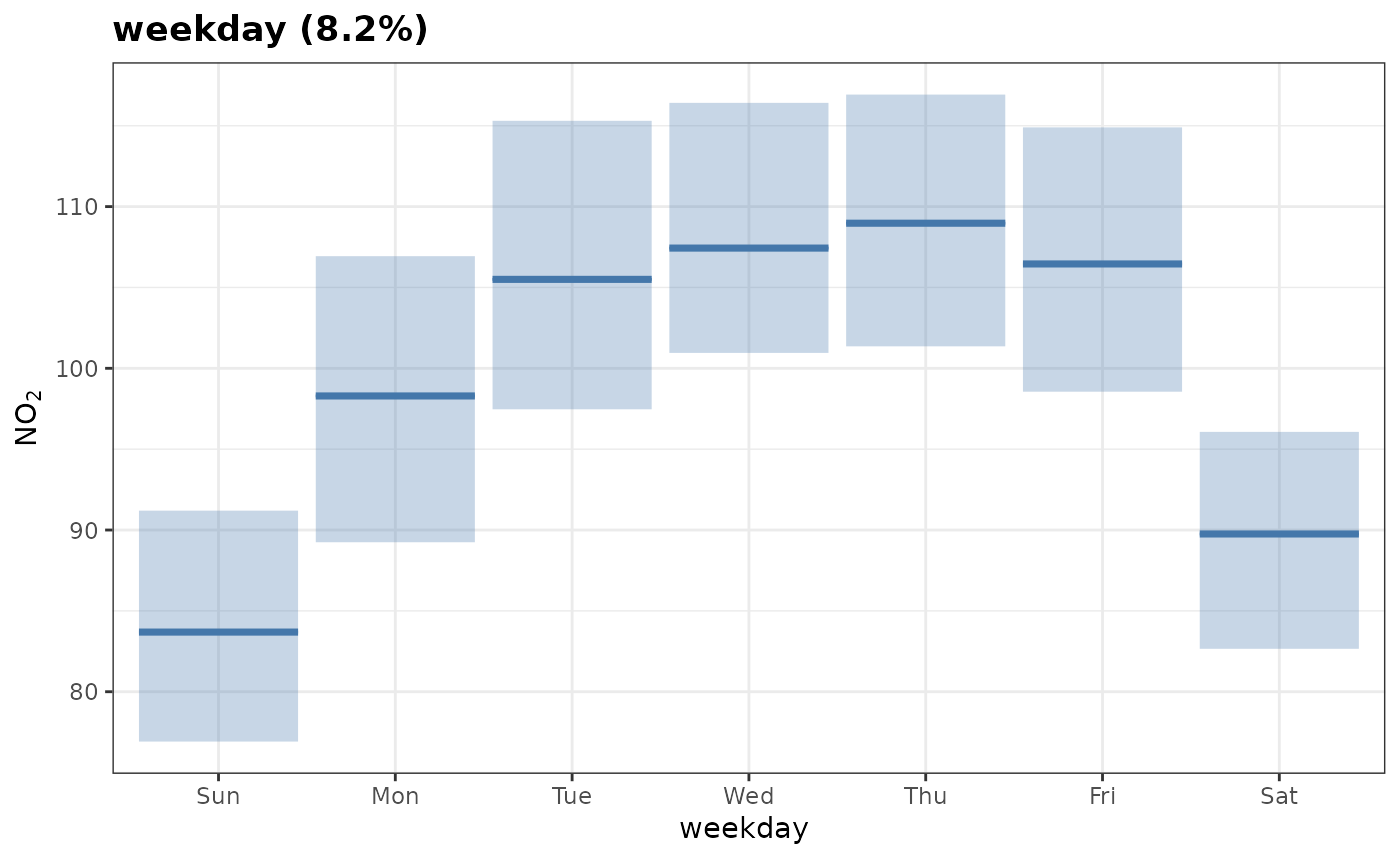

A categorical variable like weekday looks slightly

different, but achieves a similar result. no2 is lowest on

weekends, all else being equal.

plot_dw_partial_1d(no2_model, "weekday", n = 100)

If a variable isn’t given, all variables will be plotted in a

patchwork assembly in order of importance.

plot_dw_partial_1d(no2_model, n = 100)

Grouped PD

Sometimes, when examining partial dependences, it is useful to consider grouped partial dependences. This means, before PDs are calculated, we split the data into groups and calculate PDs for each subset of the data. Let’s give this a go now.

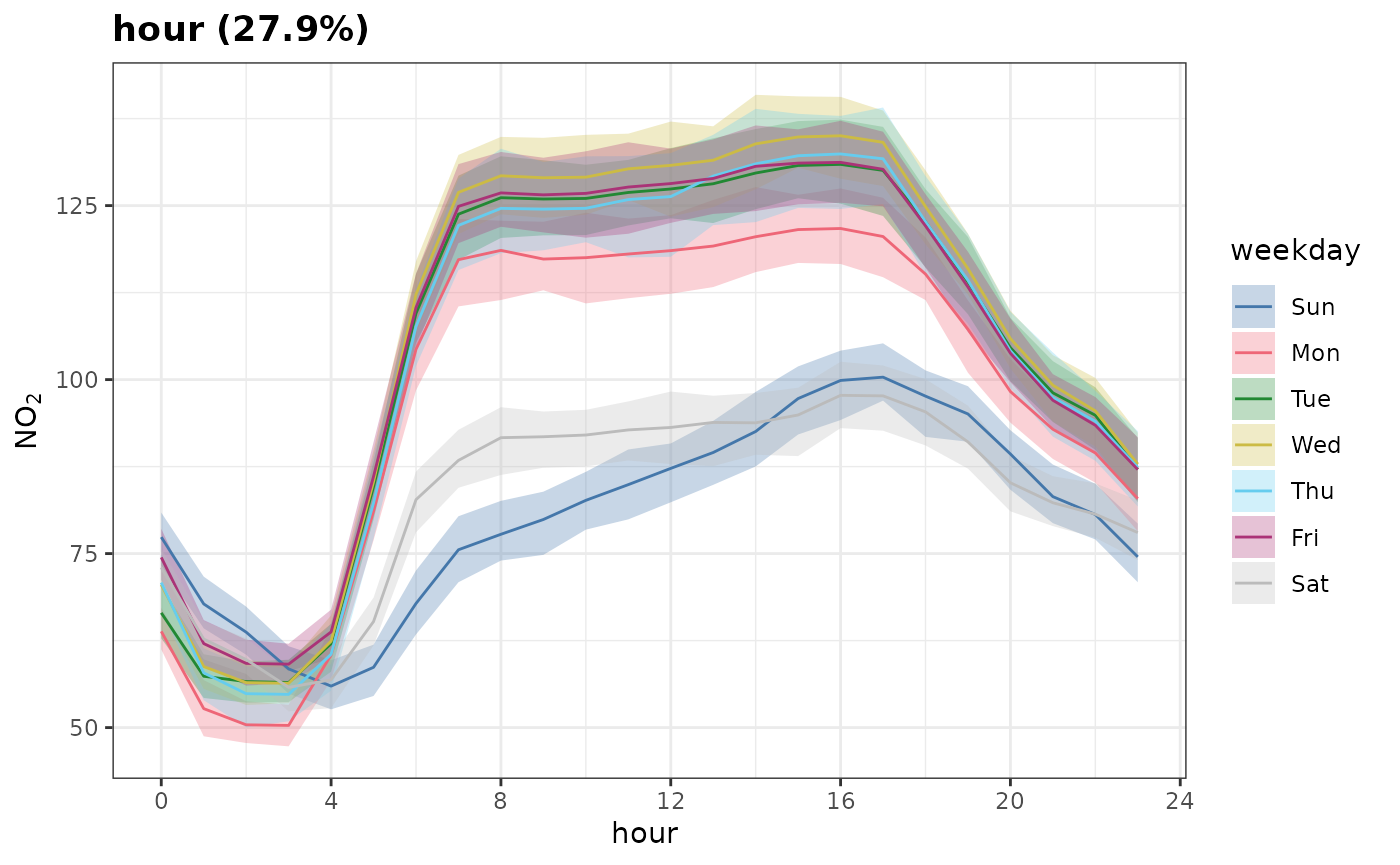

plot_dw_partial_1d(no2_model, "hour", group = "weekday", n = 1000)

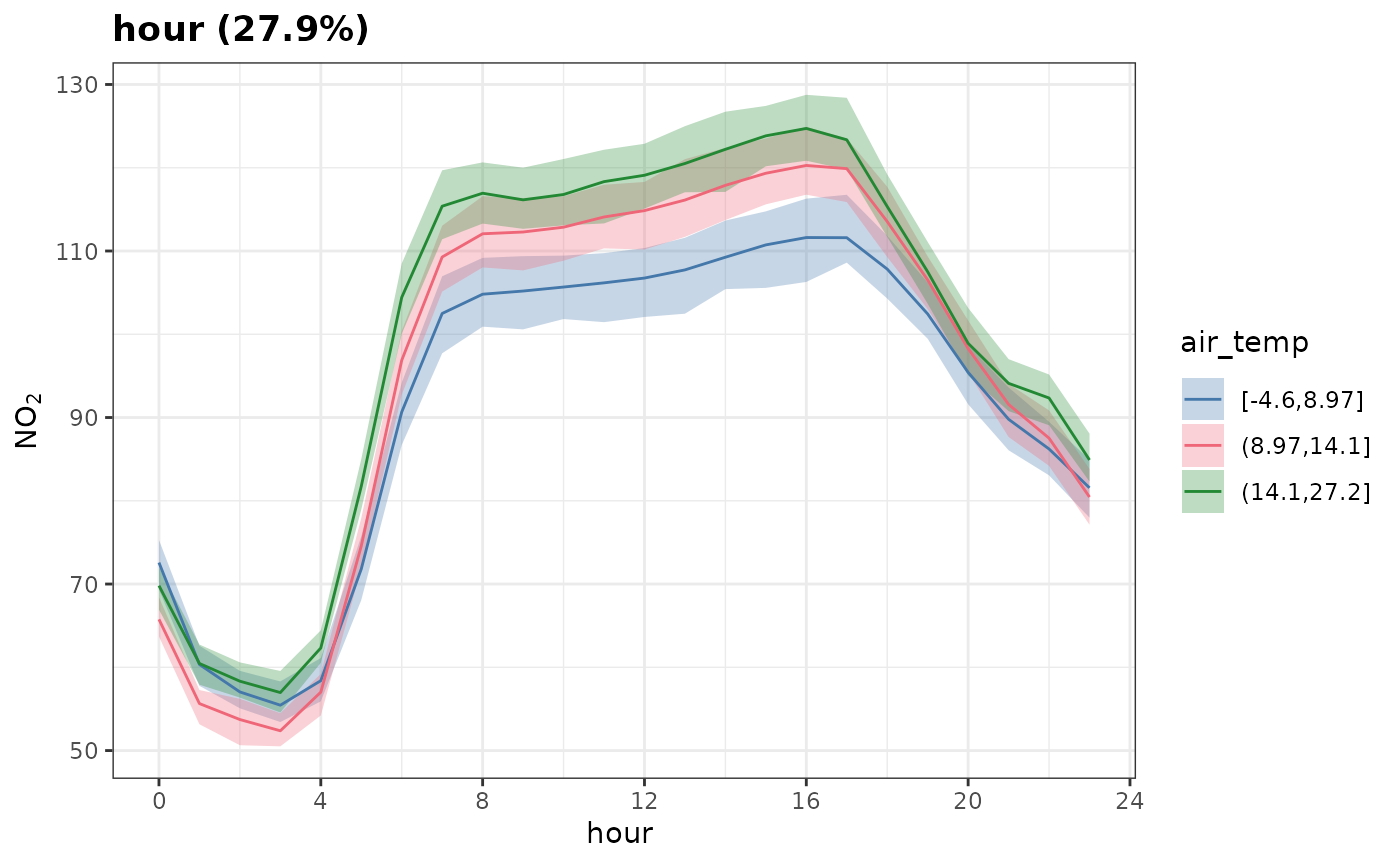

Note that group need not be categorical; you may provide

a continuous variable which will be binned into

group_intervals. Here we group by "air_temp"

and split it into 3 equally sized bins.

plot_dw_partial_1d(

no2_model,

"hour",

group = "air_temp",

group_intervals = 3L,

n = 1000

)

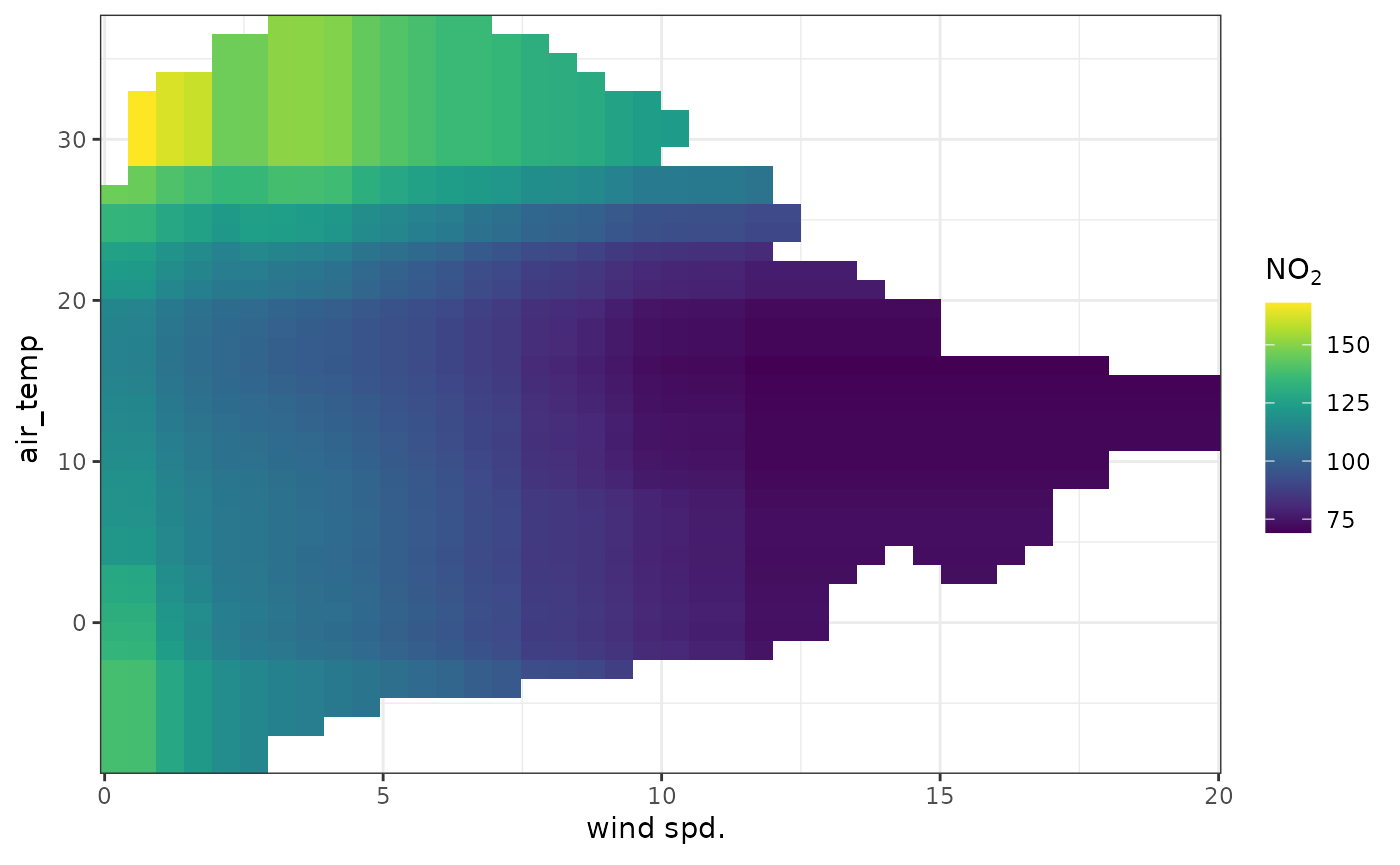

Two-Way Interactions

Above we needed to treat one of our continuous features as a factor feature.

It can be very useful to plot important two-way interactions. In this

example the interaction between "ws" and

"air_temp" is considered. The plot shows that

no2 tends to be high when the wind speed is low and the

temperature is low, i.e., stable atmospheric conditions. Also

no2 tends to be high when the temperature is high, which is

most likely due to more O3 available to convert NO to

NO2. In fact, background O3 would probably be a

useful covariate to add to the model.

plot_dw_partial_2d(no2_model, "ws", "air_temp", n = 200)

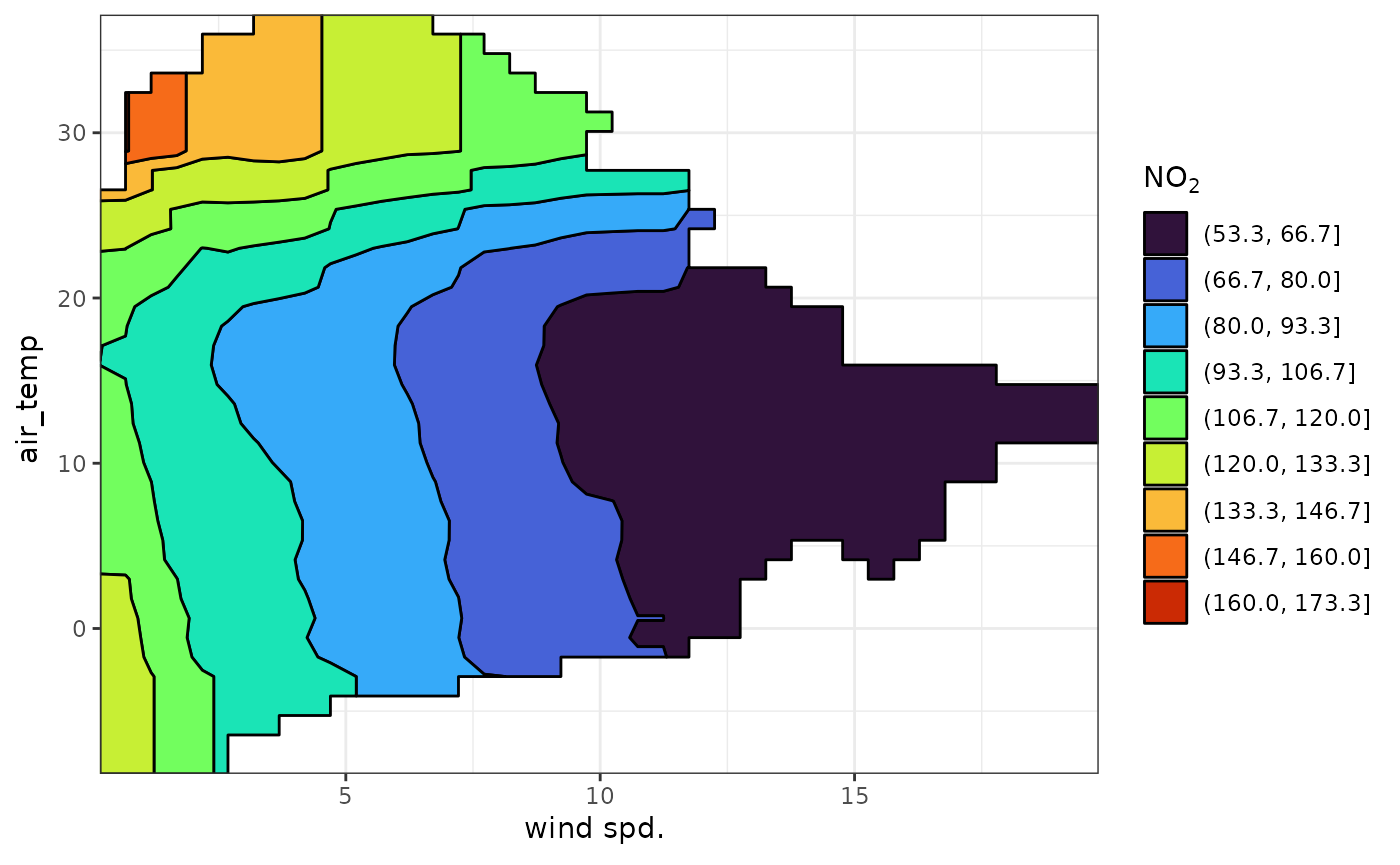

It can be easier to see some of these relationships using a binned

scale. contour = "lines" will overlay the continuous colour

surface with contour lines. contour = "fill" will bin the

entire colour scale. The number of bins is controlled using the

contour_bins argument.

plot_dw_partial_2d(

no2_model,

"ws",

"air_temp",

n = 200,

contour = "fill",

contour_bins = 10,

cols = "turbo"

)

Customisation

These plots can be customised like any other ggplot2 object.

library(ggplot2)

plot_dw_partial_1d(no2_model, "hour", group = "weekday") +

theme_light(14) +

theme(

title = element_text(face = "bold"),

plot.subtitle = element_text(face = "plain", size = 11),

legend.position = "none"

) +

scale_fill_manual(

values = c(

"orange",

"cadetblue",

"lightblue4",

"lightblue3",

"lightblue2",

"lightblue1",

"orange3"

),

aesthetics = c("fill", "color")

) +

labs(

x = "Hour of the Day",

y = "NOx (ug/m3)",

fill = "Weekday",

color = "Weekday",

subtitle = "Weekends (orange) have lower NOx emissions than weekdays (blue)."

) +

scale_y_continuous(limits = c(0, NA)) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = seq(0, 24, 4), expand = expansion())

#> Scale for fill is already present.

#> Adding another scale for fill, which will replace the existing scale.

#> Scale for y is already present.

#> Adding another scale for y, which will replace the existing scale.

#> Scale for x is already present.

#> Adding another scale for x, which will replace the existing scale.

A thoroughly customised partial dependence plot.

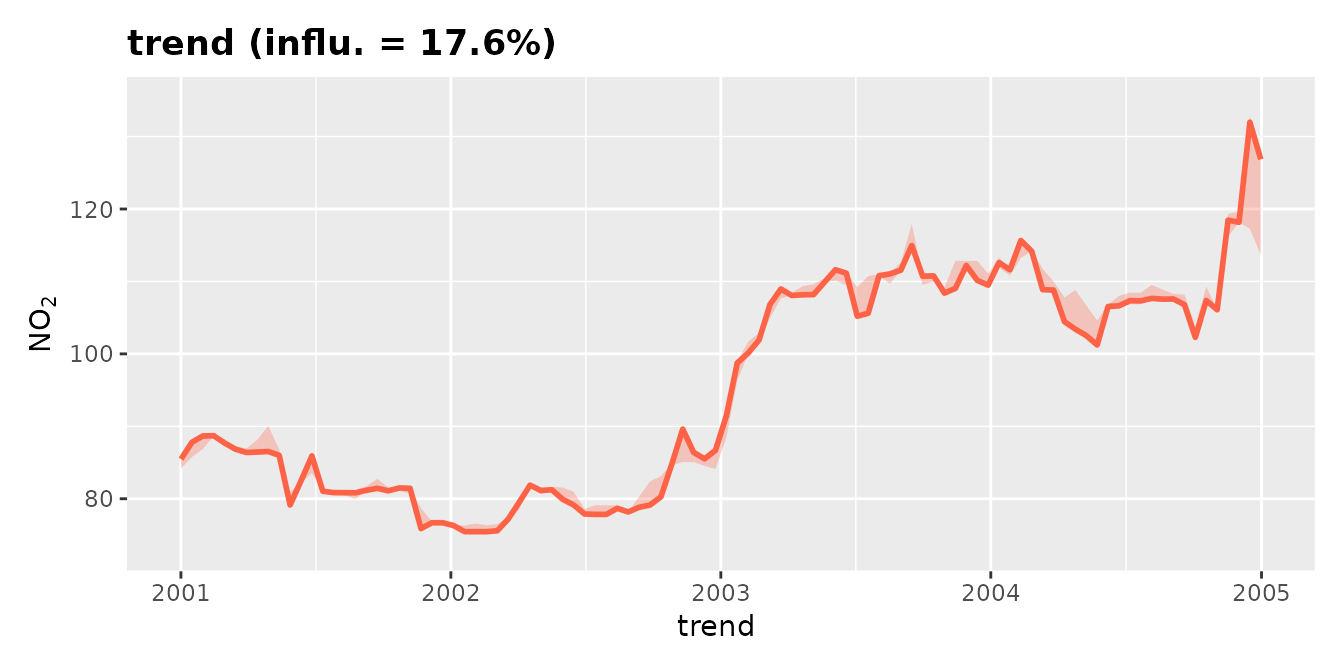

Apply meteorological averaging

An indication of the meteorologically-averaged trend is

given by the plot_dw_partial_1d() function above.

plot_dw_partial_1d(no2_model, "trend", n = 100, intervals = 100)

A much better indication is given by using the model to predict many

times with random sampling of meteorological

conditions. This sampling is carried out by the

simulate_met() function.

Note that you’d typically want n to be a higher value

than what’s used in this example; it has been set to 50 for

speed. Recall also that some mirai::daemons() are set to

allow for parallelism.

demet <- simulate_dw_met(

no2_model,

vars = c("ws", "wd", "air_temp"),

n = 50

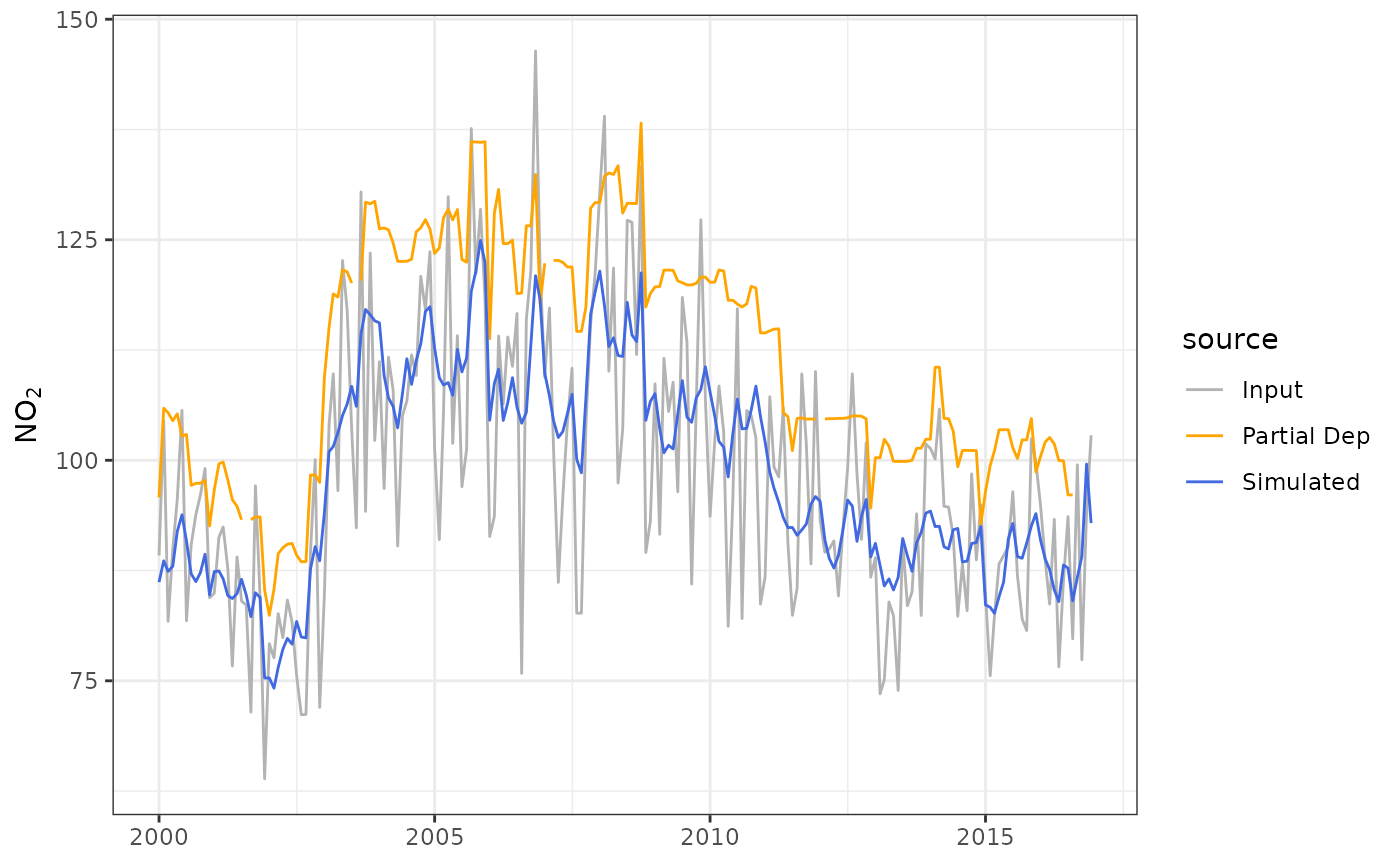

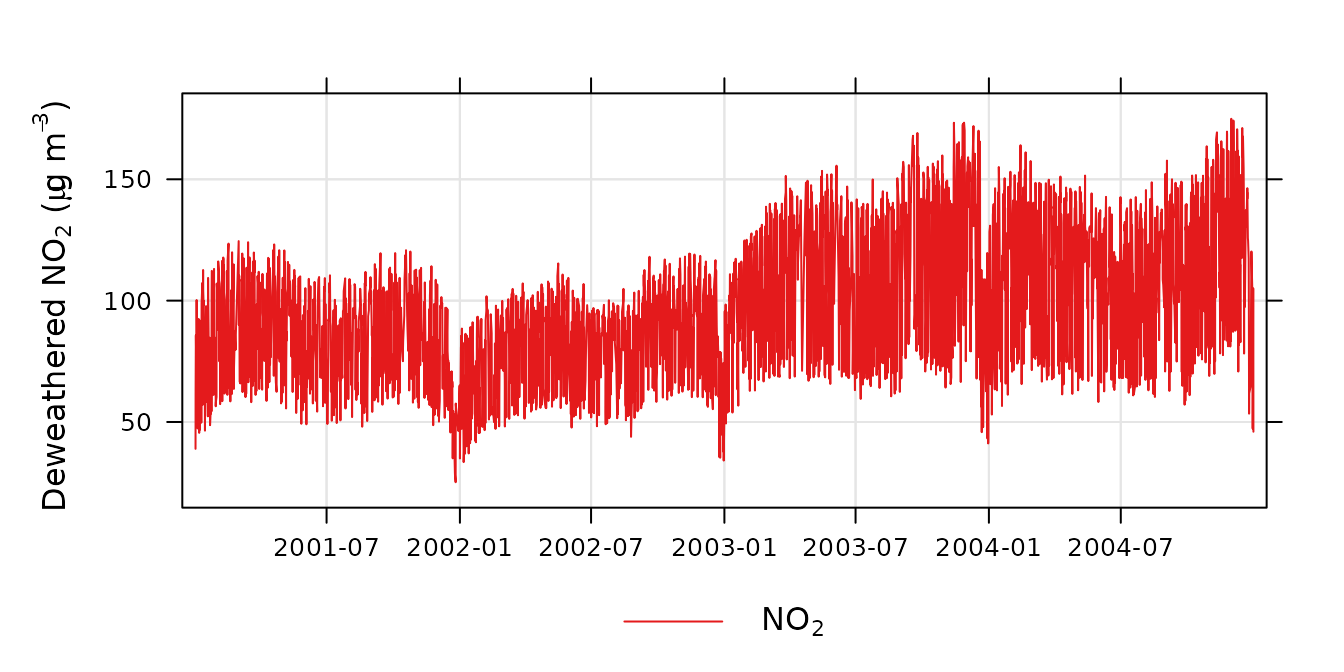

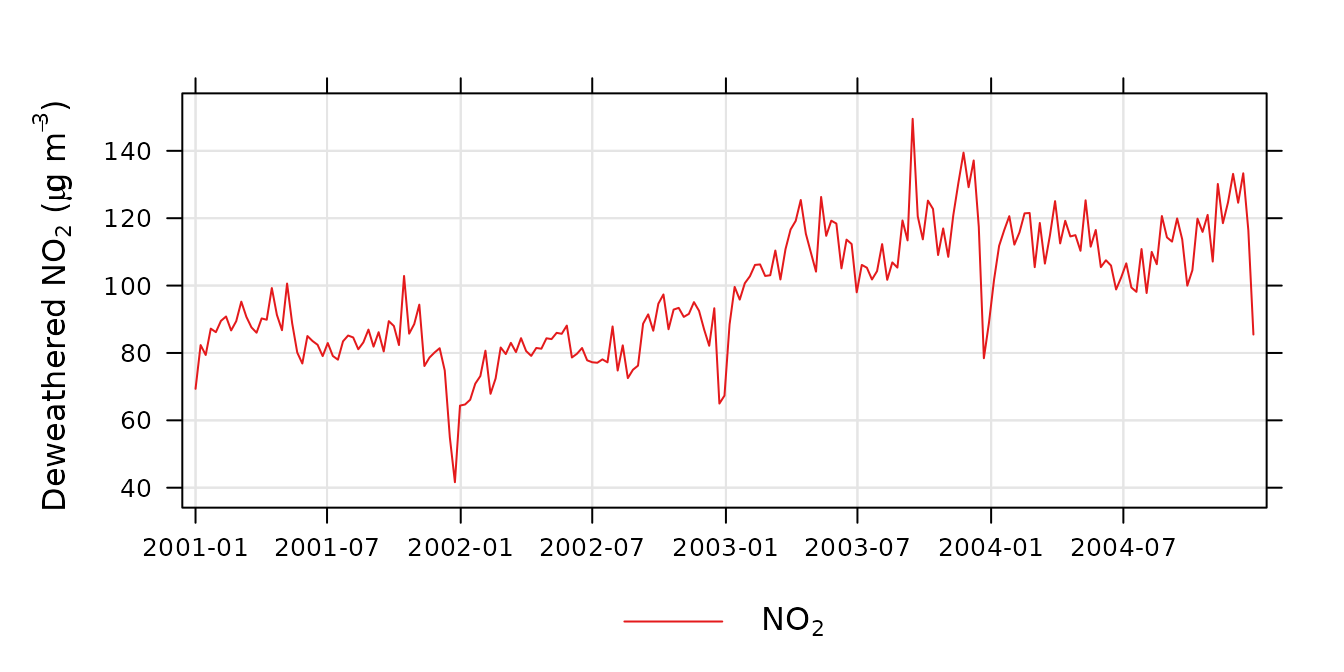

)Now it is possible to plot the resulting trend. The

plot_sim_trend() function is a convenient way to do so.

plot_sim_trend(demet)

A deweathered nitrogen dioxide trend.

The plot shows the trend in NO2 controlling for the main weather variables. The plot now reveals the strong diurnal and weekly cycle in NO2 that is driven by variations in the sources of NO2 (NOx) rather than meteorology, i.e., road traffic which has strong hourly and daily variations throughout the year. It can be useful to simply average the results to provide a better indication of the overall trend. For example:

plot_sim_trend(demet, avg.time = "month")

A time-averaged deweathered nitrogen dioxide trend.

It can be useful to compare this simulated trend to the original

input data. plot_sim_trend() can be provided the model used

to construct demet to overlay both on the same plot. Also

useful to highlight is the .plot_engine argument, which

supports "ggplot2" for static plots and

"plotly" for interactive plots;

plot_sim_trend() using the plotly engine

provides useful tooltips, zooming, and the ability to toggle the

different traces on and off.

plot_sim_trend(

demet,

dw = no2_model,

avg.time = "week",

.plot_engine = "plotly"

)Note that the function predict_dw() is also provided for

generalised use of a deweather model for prediction.